92 journalists killed, 41 media professionals injured, 329 media outlets shut down, 112 journalists captured, 30 media workers still in Russian detention, persecution, intimidation and death threats to journalists, working despite constant risk to one’s life and health, blackouts and searches for new way to work amidst a crisis. Most of these numbers are about Ukrainian media outlets and media professionals who were faced with a new reality on the morning of February 24, 2022. Regardless of where they are – in the areas relatively safe or far from the battlefield, in frontline cities, or working underground in the occupied territories – Ukrainian media face all kinds of threats and challenges due to the full-scale war. All media outlets without exception have made their way from shock to developing new algorithms to work during Russia’s armed aggression. Some did not survive. Some were destroyed by the Russian occupiers. Some relocated and remain a source of support for the audience who, like these media outlets, lost their home and land. Some have set new work standards that are changing journalism at large.

In late 2022, almost a year after the start of Russia’s war on Ukraine, an IMI study showed virtually no hate speech in the war-related news by regional media outlets. This was despite Russia’s systematic crimes against media professionals in particular and Ukrainians and Ukraine in general. Despite the large share of war-related in the media (50% of all content), only 0.3% of news contained hate speech, which is a striking result. Overall, 93% of the news cited reliable sources of information, as evidenced by another IMI study conducted in 2023. In general, wartime journalism is characterised by an increase in the news’ reliability. The war boosted adherence to standards: only 1.5% of regional news mixed up facts and comments. For comparison: in 2021, 11% of regional news reports failed to delineate between facts and comments.

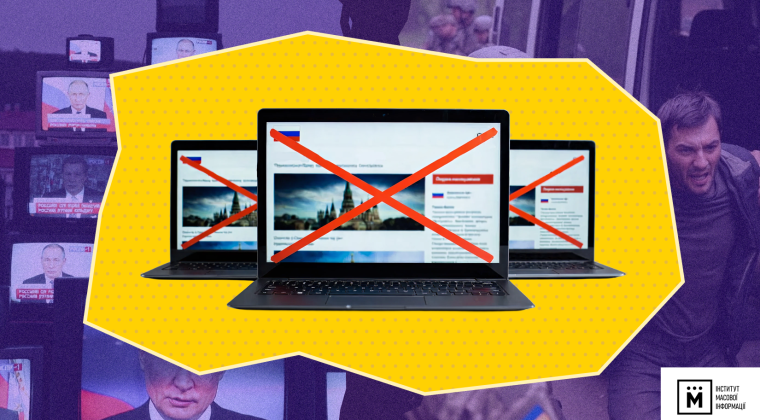

All this is happening amidst Russia’s constant attacks on Ukrainian media, which have been going on for 1,000 days. As of early November 2024, Russia has committed at least 664 crimes against the Ukrainian media (including regional media outlets).

2022: Switching to wartime journalism

The majority of Ukrainian media outlets reacted to the shock of the war by switching to working round the clock. In the first days of the war, this happened throughout Ukraine: in the regions where hostilities had begun, in those under long-range attacks by Russian missiles, and in those that can be roughly considered the rear areas. Essentially, all media outlets that continued to work through the first weeks and months of Russia’s full-scale offensive transitioned to wartime journalism.

That period had the following characteristics.

![]() For the media in frontline cities and communities: deciding to close or relocate their offices; high risks for the media professionals, who worked with no safety gear in that time; media offices working 24 hours a day; Russian troops targeting TV towers; the threat of being perceived as a saboteur or spy; a sharp rise in demand for information; a radical growth in demand for information from social media, in particular from Telegram.

For the media in frontline cities and communities: deciding to close or relocate their offices; high risks for the media professionals, who worked with no safety gear in that time; media offices working 24 hours a day; Russian troops targeting TV towers; the threat of being perceived as a saboteur or spy; a sharp rise in demand for information; a radical growth in demand for information from social media, in particular from Telegram.

In the first days of the full-scale war, 60% of local and regional broadcasters and 54% of program service providers in Sumy found themselves in an active combat zone. Chernihiv oblast, too, was one of the first regions to become an area of hostilities. Local newspapers were the first media outlets to shut down, since printing and distributing new issues became impossible. However, some journalists with the local TV channels Suspilne Chernihiv, Novyi Chernihiv, Dytynets, and some local websites stayed in the city despite the hostilities. Despite the blackouts and mobile connection being absent in Chernihiv for about three weeks due to constant Russian shelling, not a single TV channel stopped working.

In Kharkiv oblast, the Russian troops reached the highway encircling the city on the first day. Almost immediately, journalists began to report on the developments, working day and night. In the first days of the invasion, Russian troops shelled the TV tower in Kharkiv and Izyum.

In Mykolaiv and other cities, local journalists found it virtually impossible to work amidst the hostilities, as local media professionals had no safety gear. From the first day of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and until mid-March 2022, Sumy media workers also had no proper protection (body armor and helmets) and worked at their own risk. This was the case in nearly all oblasts. For example, Dmytro Smolenko, Zaporizhzhia-based photo correspondent for Ukrinform, said in an interview with the IMI that it was as late as a month into Russia’s aggression that he received a set of body armor, a first aid kit, and everything necessary for safer work thanks to the Institute of Mass Information. In fact, in the first months of the war, the IMI provided safety gear to all journalists who needed it.

![]() For Ukrainian media in the occupied territories: widespread suspension of regional media outlets; Russia blocking Ukrainian broadcasting; regional Ukrainian journalists being captured, kidnapped, and detained; media teams in the occupied territories facing threats, intimidation, and seizure of their offices; television towers being seized.

For Ukrainian media in the occupied territories: widespread suspension of regional media outlets; Russia blocking Ukrainian broadcasting; regional Ukrainian journalists being captured, kidnapped, and detained; media teams in the occupied territories facing threats, intimidation, and seizure of their offices; television towers being seized.

In the first weeks of the invasion, the occupiers turned off Ukrainian TV channels in Kherson oblast and replaced them with Russian channels on T2 a day later. In Henichesk (Kherson oblast), two local websites and a newspaper announced they were putting their work on hold. A few days later, the kidnappings of journalists began: on March 11, 2022, local activist and journalist Serhiy Tsyhipa was kidnapped in Nova Kakhovka, and the next day, local journalist Oleh Baturyn went missing in Kakhovka. The occupied part of Zaporizhzhia oblast saw the same situation. The most high-profile cases since the beginning of the war include the abduction and detention of UNIAN correspondent Iryna Dubchenko, the kidnapping of journalists with the Melitopol media holding MV-Plus, and the father of Melitopol-based editor Svitlana Zalizetska being taken hostage.

Media outlets were shutting down and journalists were persecuted in Luhansk oblast as well. Since the start of Russia’s invasion, most media outlets in Luhansk oblast have either ceased operations or put them on hold. For instance, newspapers such Visti Bilovodshchyny, Zhyttya Bilokurakynshchyny, Slovo Khliboroba (Mylove village), and Kreminshchyna. Some online publications resumed work after their employees left for safe places.

In the parts of Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts occupied after February 24, the Russian troops disabled Ukrainian TV channels and radio stations and blocked access to Ukrainian websites immediately as well. The journalists who remained there faced intense psychological pressure, persecution, and intimidation. The situation was the same in Mariupol in particular.

All media outlets in the unoccupied part of Donetsk oblast, namely the TV channels TV7, MTV, and SigmaTV, stopped working in Mariupol completely. Their studios and offices have since been destroyed. Non-news projects and the newspaper Pryazovskyi Rabochyi have closed down and the news websites mrpl.city, 0629.com.ua, and others have relocated.

![]() For relatively safe (rear) regions: consistent spread of fake news and Russian disinformation through extensive networks of Telegram channels; numerous DDoS attacks on regional media; death threats and intimidation of media offices and their employees through mass emails from Russia; the risk of being perceived as a saboteur or spy; attacks on TV towers; the first journalist lives lost.

For relatively safe (rear) regions: consistent spread of fake news and Russian disinformation through extensive networks of Telegram channels; numerous DDoS attacks on regional media; death threats and intimidation of media offices and their employees through mass emails from Russia; the risk of being perceived as a saboteur or spy; attacks on TV towers; the first journalist lives lost.

Poltava media offices were have had to fight off DDoS attacks since the first days of the full-scale invasion. The enemy especially targeted the websites of Poltavska Khvylia, Poltavshchyna, Zmist, and the YouTube channel PTV UA.

Zhytomyr has faced an unprecedented amount of fake news and media manipulation since the beginning of the full-scale war. DDoS attacks on regional media became more frequent in that oblast, too.

In Cherkasy, Kropyvnytskyi, and Ternopil, all media continued to work. Here, the media workers focused on building quick communication with the authorities and on countering Russian disinformation and DDoS attacks. For example, in Ternopil, the websites Realno, TMC.INFO, 0352.ua, and Teren were affected. The Russians actively targeted the Volyn news agency Konkurent and, as in Zaporizhzhia, actively sent death threats and intimidating emails to regional media offices.

In several oblasts, journalists were exposed to danger due to the anxiety among citizens, who perceived correspondents as potential saboteurs or spies helping the enemy to target their fire.

Vinnytsia remained a fairly calm region despite sharing a segment of the border with “Transnistria”. Local media also struggled with fake news and opposition to reporting vital information from local authorities.

The media began losing their journalists as soon as the first weeks of the war. In Lviv, journalists Viktor Dudar and Yuriy Oliynyk died as combatants. Two Zaporizhzhia journalists, Oleh Yakunin and Oleh Shemchuk, died defending Ukraine in 2022. Now there are media outlets mourning their colleagues in Ukraine’s every oblast.

2023: Exhaustion, blackouts, access to information

The second year of the war was a year of blackouts and lack for Ukrainian media. This included understaffing, severe mental exhaustion, financial difficulties, and increased resistance on the part of the officials to provide necessary information to media professionals.

![]() Blackouts. Russia’s constistent efforts to destroy Ukraine’s energy infrastructure in 2023 created new challenges for regional media outlets: finding money to purchase power storage equipment, reformatting the team’s work, redistributing responsibilities and workloads – all this became a new reality for the regional media. For example, by the end of 2022, no more than 80% of companies in Sumy planned to operate during likely blackouts. As of late October 2022, none of the local and regional broadcasting companies had backup power sources and voltage stabilizers.

Blackouts. Russia’s constistent efforts to destroy Ukraine’s energy infrastructure in 2023 created new challenges for regional media outlets: finding money to purchase power storage equipment, reformatting the team’s work, redistributing responsibilities and workloads – all this became a new reality for the regional media. For example, by the end of 2022, no more than 80% of companies in Sumy planned to operate during likely blackouts. As of late October 2022, none of the local and regional broadcasting companies had backup power sources and voltage stabilizers.

Thanks to the support from the Institute of Mass Information and its partners, several hundred Ukrainian media outlets were able to resolve the issue of energy and Internet connection deficiency. Perhaps the greatest support for media professionals was the opening of first 10, and now 14, regional Mediabaza hubs by the Institute of Mass Information. As well as the tremendous efforts to meet the needs for energy equipment, which continue to this day.

![]() Lack of staff. An IMI survey from August 2023 showed that 27% of media workers had moved to other oblasts within Ukraine or abroad. All regional media outlets (from those near the frontline to those in the rear areas) exerienced understaffing. According to the IMI, from September 2023 to September 2024, only 32% of the surveyed Ukrainian media outlets managed to maintain a stable staff composition and avoid losing employees. New employees often lack the necessary expertise level.

Lack of staff. An IMI survey from August 2023 showed that 27% of media workers had moved to other oblasts within Ukraine or abroad. All regional media outlets (from those near the frontline to those in the rear areas) exerienced understaffing. According to the IMI, from September 2023 to September 2024, only 32% of the surveyed Ukrainian media outlets managed to maintain a stable staff composition and avoid losing employees. New employees often lack the necessary expertise level.

Moreover, many journalists enlisted in the Ukrainian Armed Forces. For example, from Rivne alone: ICTV correspondent Pavlo Shamshyn, NTN cameraman Artur Zhurov, Volodymyretskyi Visnyk editor Serhiy Skibchyk, cameramen Vadym Makhmudov and Pavlo Dutko, and Horyn.info chief editor Taras Davydiuk (KIA).

Many media professionals from Cherkasy also joined the army: sports journalist Maksym Haptar, Provse journalist Oleksandr Nosenko, journalist Valentyn Chernyavskyi (Novyi, Chetvertyi, and several other TV channels), journalist Serhiy Khalupinskyi. TV presenter Ninel Vlasenko abandoned journalism altogether, passed certification as a combat medic and signed a contract with the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine.

In Kharkiv, journalist Dmytro Bruk, who has been reporting on the course of the Russo–Ukrainian war since 2014, Gvara Media digital editor Dmytro Zhabotynskyi, who produced social media content and edited videos, and Anton Alokhinson (Liuk) enlisted in the army.

Throughout 2023, many media outlets continued to lose their colleagues who were killed in action while defending Ukraine from the Russian invaders.

![]() Lack of strength. While 72.4% of surveyed Ukrainian journalists believed in our victory in 2022, this figure had dropped by more than half, to 31.5%, in 2023, as shown by the IMI survey on mental health challenges faced by journalists. Indeed, in the first months and even the first year of the war, most media professionals were too busy to process stress. The radical changes that the full-scale invasion indroduced into the life, work, duties, and others’ needs displaced the awareness of one’s own mental health troubles. But this could not continue indefinitely. In 2023, 98% of Ukrainian media professionals reported stress. The share of media workers who felt tired, had sleep issues, experienced depression and hopelessness increased noticeably (almost threefold, to be precise).

Lack of strength. While 72.4% of surveyed Ukrainian journalists believed in our victory in 2022, this figure had dropped by more than half, to 31.5%, in 2023, as shown by the IMI survey on mental health challenges faced by journalists. Indeed, in the first months and even the first year of the war, most media professionals were too busy to process stress. The radical changes that the full-scale invasion indroduced into the life, work, duties, and others’ needs displaced the awareness of one’s own mental health troubles. But this could not continue indefinitely. In 2023, 98% of Ukrainian media professionals reported stress. The share of media workers who felt tired, had sleep issues, experienced depression and hopelessness increased noticeably (almost threefold, to be precise).

According to both Ukrainian and foreign journalists working in Ukraine, the new challenges that arose after the war’s escalation in 2022 were uncertainty and a sense of danger. These were caused by the constant shelling targeting Ukraine’s entire territory without exception and not having a safe place where one could rest and catch their breath. This leads to the loss of stability, inability to plan anything, and a sense of uncertainty. After all, each new shelling strike may change the energy situation, any relatively safe place may get destroyed, the list goes on forever.

![]() Lack of money. After the “hot phase” of experiencing the war came to an end in 2023, the media faced financial problems that had accumulated over the first year of the full-scale invasion. The decline, and sometimes destruction of advertising markets in the regions, the crisis in Ukraine’s economy overall pushed many media to the brink of survival. In Chernivtsi, as in many other oblasts, journalists started working more and earning less. Not all media outlets emerged from the year-long financial crisis, and local print newspapers had an especially rough time of it. A solution the regional media discovered was to abandon the printed versions of the newspapers and switch to online reporting. There have also been some positive developments. For example, in Poltava, the media seemed to have stabilized their operations in the second year of the full-scale war: not a single website stopped updating. Still, two other newspapers there did close down during this period. Rivne, which is considered a rear area, saw a similar situation. However, despite many media outlets having lost their income in the first months of the big war, some of them were able to improve their financial situation a year later. However, financial survival remains the number one issue for Ukraine’s regional media.

Lack of money. After the “hot phase” of experiencing the war came to an end in 2023, the media faced financial problems that had accumulated over the first year of the full-scale invasion. The decline, and sometimes destruction of advertising markets in the regions, the crisis in Ukraine’s economy overall pushed many media to the brink of survival. In Chernivtsi, as in many other oblasts, journalists started working more and earning less. Not all media outlets emerged from the year-long financial crisis, and local print newspapers had an especially rough time of it. A solution the regional media discovered was to abandon the printed versions of the newspapers and switch to online reporting. There have also been some positive developments. For example, in Poltava, the media seemed to have stabilized their operations in the second year of the full-scale war: not a single website stopped updating. Still, two other newspapers there did close down during this period. Rivne, which is considered a rear area, saw a similar situation. However, despite many media outlets having lost their income in the first months of the big war, some of them were able to improve their financial situation a year later. However, financial survival remains the number one issue for Ukraine’s regional media.

![]() Lack of information. 2023 saw a deterioration in the communication between the media and regional authorities. In many oblasts, officials started withholding information about the impact of Russian missile strikes, the situation in communities, and the casualties. The Sumy Oblast Military Administration may be considered one of the most secretive regional authorities today. For over a year, since 2023, the regional leadership has been disregarding the journalists’ (and, indeed, the community’s) basic right to receive information about the impact of the missile strikes, the evacuation, and other information which is, without exaggeration, vital.

Lack of information. 2023 saw a deterioration in the communication between the media and regional authorities. In many oblasts, officials started withholding information about the impact of Russian missile strikes, the situation in communities, and the casualties. The Sumy Oblast Military Administration may be considered one of the most secretive regional authorities today. For over a year, since 2023, the regional leadership has been disregarding the journalists’ (and, indeed, the community’s) basic right to receive information about the impact of the missile strikes, the evacuation, and other information which is, without exaggeration, vital.

In Zaporizhzhia, the communication crisis involving the oblast military administration lasted almost throughout 2023. For over a year of the full-scale war, journalists faced unresolved issues in appointing spokespeople. Regional media outlets also faced challenges while talking with press officers. The communication varied greatly depending on a spokesperson’s personality: from complete disregard for the professional rights and needs of journalists to an amiable attitude towards their work.

The war also exacerbated the issues with the law on access to public information. In 2022–2023, journalists faced consistent refusals from officials to provide answers to journalistic queries. Postponing a query indefinitely (until the end of the war) has become a lifesaver for regional officials.

In Ternopil, Poltava, Khmelnytskyi, regardless of whether they were in the “rear” or frontline areas, officials did their best to avoid healthy communication with the media. For example, in Poltava, City Council sessions became an acceptable space for deputies and officials to openly threaten journalists. And the Khmelnytskyi City Council stopped inviting journalists to extraordinary meetings for over a year, all while filming crews from the municipal TV channel Misto were constantly present at them. This only changed in late March 2023, when all media representatives were at last invited to an extraordinary meeting in advance, provided with the agenda, and only asked not to livestream the session. But this did not last long.

2024: A thousand reasons to persevere

The media that survived met day 1000 of the full-scale war with adapted work routines, new ideas and new teams that opened in the regions during the war. However, the most prominent feature of the Ukrainian media field 1000 days into the war is consolidation and unity. Russia’s aggression has done what was not always possible in the relatively peaceful times: media professionals have been uniting into powerful clusters that have been resisting evil on the ground for almost three years, uniting into even larger cross-regional communities for mutual support and assistance. The Media Movement community, which currently unites about 70 media outlets, is increasingly asserting itself.

Since the beginning of the war, the IMI has been helping regional journalists meet their needs for safety gear and training (namely in first aid and applying for grant support). During the first 100 days of the full-scale war, the IMI provided media workers with 1,111 bulletproof vests, over 900 helmets, over 300 pairs of ballistic goggles, 750 first-aid kits, and more than 1,000 other medical supplies. And that was just the beginning. Computers, phones, including satellite phones, Starlinks, evacuation assistance, medical assistance, overall help. As of now, there has been over ten thousand cases of the IMI providing aid. Im the 1,000 days of the full-scale war, the IMI team collected (and continues to collect) and provided (and continues to provide) the needed protective and power equipment, mental health support, and financial assistance to journalists.

On the 1000th day of the war, each and every media professional can say how difficult it has been to endure this horror of the war for so many days. But we must hold on. And persevere. Because we will need no less, and perhaps even more resources for the post-war life to come.

Natalia Vyhovska