Documenting Russia’s crimes against the media is more than just collecting statistics. Behind every number are human lives, the details of their work or death. The specialists working to verify and analyse this data do not just record facts, but also let real stories pass through themselves. This is painstaking work necessary to amass an evidence base, fight Russian propaganda and achieve future prosecution.

Kateryna Dyachuk, senior freedom of speech monitor at the Institute of Mass Information, is records Russia’s crimes against the media and journalists as part of the Freedom of Speech Barometer. In a new interview, she discussed the following:

- How personal contacts and an extensive regional network help the IMI monitor Russia’s crimes against the media

- From amendments to Decree No. 73 to defending the rights of journalists on the ground

- Primary sources are the backbone of verification

- “To you it’s statistics, but to me the whole world has died.” The ethical dilemma of getting verification from families

- From chaos, we created system. How the IMI started documenting Russia’s crimes on the first day of the full-scale war

- How to tell the Freedom of Speech Barometer apart from the Monitoring Study of Russia’s Crimes against Journalists and the Media

- Why the different figures? Whose data to trust: those by local organizations or international ones?

- Documenting losses. How to document the truth while reining in the emotions

How personal contacts and an extensive regional network help the IMI monitor Russia’s crimes against the media

“What data the Institute of Mass Information’s Monitoring Study of Russia’s Crimes Against Journalists and the Media is based on and how do you collect information?”

“Information is primarily collected from open sources, as well as from journalists contacting the IMI. We have the Internet, we have social media, we monitor the media space. We have a regional network of 20 IMI representatives contacting local journalists. If an incident occurrs, journalists, knowing that the IMI monitors Russian crimes, contact our representatives and report what happened. We also source already fully processed information from the media.

“This is how it happens in practice: we see reports in open sources, contact the media worker, check and ask what happened. Our regional network also collects information, so journalists contact us directly and let us know if something happens.

“To give an example: Russia’s mass shelling on Kharkiv in 2024, when several journalists were injured while covering the aftermath of the strikes on civilian infrastructure, including Viktor Pichuhin, a journalist with the Nakypilo media group. He later told our regional representative Yulia Napolska that the explosion had gone off near him and that he was very lucky to have survived. Viktor came under fire when the Russians double-tapped a residential building where rescuers were already at work. This is how we collect information, although sometimes contacting a person immediately after such a strike is awkward, because we understand that it may not be the best time to ask for comments.”

Viktor Pichuhin in a bomb shelter. Photo by Viktor Pichuhin

From amendments to Decree No. 73 to defending the rights of journalists on the ground

“The IMI has initiated and joined many task forces with state bodies aiming to improve reporters’ working conditions, to combat impunity. For example, the IMI was actively involved in the President’s Office task force on developing the amendments to the UAF Commander-in-Chief’s Decree No. 73 on improving the interaction between the military and journalists. We also actively cooperate with the Prosecutor General’s Office, we are in touch with the Security Service of Ukraine. So journalists know that they can contact us and do often complain to the IMI about facing restrictions by the authorities. We try to resolve these issues, sometimes off the record, sometimes publicly, when media workers unite and come out with addresses.

“Our journalists actively respond and nudge IMI representatives in the regions. For example, the Russians are shelling our cities, infrastructure. Journalists go to report on these crimes and are hindered by law enforcers, local authorities, or some other persons. Knowing that the IMI records such cases, the journalists report them to us.

“Take the strike on an educational institution in Poltava, when many cadets died and journalists had issues with accessing the site. The Poltava representative of the Institute of Mass Information, Nadia Kucher, coordinated between the journalists and the authorities on allowing Ukrainian and foreign reporters access. We also included these cases in the Freedom of Speech Barometer. In that instance, the delay in reporting played into the hands of anonymous Telegram channels, which had a window of opportunity to spread misinformation.”

Primary sources are the backbone of verification

“What are the main sources that the IMI relies on when verifying data?”

“Primary sources. Of course, we try to contact the injured journalists right away to get information firsthand or from the media outlet they work with. We also check the reports with colleagues, other journalists, this is done by our regional representatives. We check whether the person who contacted the IMI really works in journalism, as well — simply having an ID badge is not enough for us. In some cases, we search for and read or watch some of the news stories made by this journalist or the media outlet to better understand the situation. This is what verification is all about. We can also take information from reliable media outlets. In fatal cases, we make sure to contact the victim party, to clarify details, to add a firsthand comment.

“After all, we realize that on social media it often so happens that some piece of information was reported by a brother, some other by a close friend, and then the local authorities added some more. I can recall cases of journalists who had enlisted in the Ukrainian Armed Forces and were killed in action. Someone reported one date or place of death, then the City Council of the journalist’s hometown posts different data. So we definitely do check.”

“To you it’s statistics, but to me the whole world has died.” The ethical dilemma of getting verification from families

“The IMI also gets verification from relatives, as far as I know.”

“We do try, but in reality this is a delicate issue. We run into it constantly with our regional representatives. Say, a journalist was considered missing for a long time, and then their body is brought back. The DNA test confirms that it is them, so they are declared dead. The person was considered missing for over a year, their relatives had some hope, even though they realized that the jouralist might be deceased. But it’s painful nonetheless.

“Contacting them is an option, yes. But when a person has just died and the relatives are busy sorting out the funeral, the process itself, then we see it as unethical to contact them at such a moment and ask. We try to do this through some friends, colleagues, intermediaries. But I cannot allow myself to do this directly. I believe that we should just let the person live through this pain, because they have a lot on their plate as it is. They may say, ‘To you it’s statistics, but to me the whole world has died,’ and they will be right.”

From chaos, we created system. How the IMI started documenting Russia’s crimes on the first day of the full-scale war

“My next question takes us back three years. What were the biggest challenges the IMI faced in terms of data verification in 2022, when you were just starting to work on the Monitoring Study of Russia’s Crimes against Journalists and the Media? And how did you overcome these challenges?”

“Everyone was in a state of intense stress and shock. No one told us what exactly needed to be done. At one point on February 24, I sat down and just started making separate notes when I saw that the crimes had begun: Russia had started killing journalists, shelling TV towers, capturing people, seizing media offices. I was already aware that a certain trend was emerging. I was already getting flashbacks about Crimea, the Donbas, and I realized that the same things would be happening in the newly occupied territories.

“There was no method to it at first. We started collecting cases. Later, as they accumulated, categories began to take shape: physical aggression, such as murders, injuring and targeting journalists; strikes on TV towers, media outlets shutting down, Ukrainian broadcasting being disabled. For example, when the Suspilne Kherson office was taken over or when many media outlets in Mariupol were taken over as well.

“Everything was very chaotic, everyone was on edge. I created a document, gave all the regional representatives access and said, ‘Guys, if something happens where you are, write the cases down there.’ Of course, they had to check the information. And we started updating this document as a news feed. From chaos, we created system — that’s how the methodology emerged.

“As for data verification, I will mention the case when a TV tower in Kyiv was first targeted with shelling. This, of course, was already a fact – you will not be going there and verifying, because it’s already real, with videos and photos all over the news. However, say, reports about the LIVE TV cameraman Yevhen Sakun, who was killed in the strike, needed verification. We had to clarify whether he should be considered as civilian casualty or as someone who died in the line of duty. We clarified this and later included him among the people who died while reporting.”

The strike on a Kyiv TV tower. Photo by Suspilne

How to tell the Freedom of Speech Barometer apart from the Monitoring Study of Russia’s Crimes against Journalists and the Media

“All these years we had been maintaining just the Freedom of Speech Barometer with violations committed by Ukrainian citizens, and now a second block has been added – the Monitoring Study of Russia’s Crimes against Journalists and the Media. The latter is released the 24th day of every month, the day the full-scale invasion started. And in the first days od each month we release a combined Barometer, which contains two blocks: the crimes committed by the Russians and the violations committed by Ukrainian citizens against journalists.

“Right after the start of the full-scale invasion, crimes against journalists and the media were only being committed by Russians. After a certain time, slowly, as Kyiv was not taken in three days, we started recording obstruction of reporting by the Ukrainian side. Some journalists faced threats, some were not allowed somewhere. For example, we recorded a surge in obstruction when the SBU began inspections at the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra. We recorded quite a few cases of violations against journalists there. Citizens of Ukraine, UOC MP parishioners, swung at journalists’ microphones, shoved them, threatened them, and interfered with their work. Again, even though they were citizens of Ukraine, their behavior was due to being brainwashed by Russian propaganda and sympathizing with Russia.”

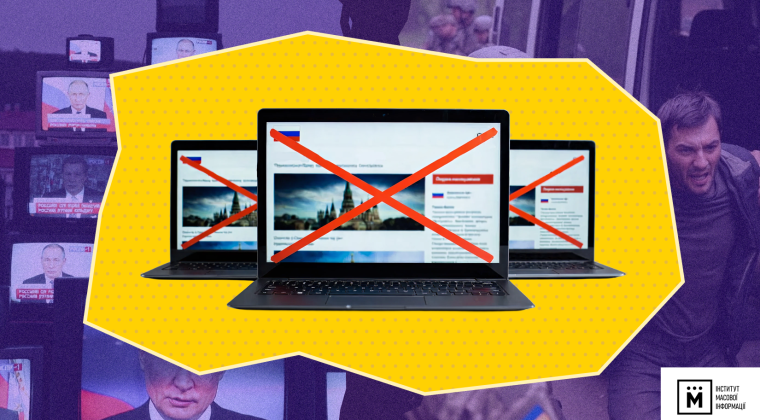

Why the different figures? Whose data to trust: those by local organizations or international ones?

“Some international organizations also keep track of crimes against journalists and the media in Ukraine. And their data is often different from ours. How should one go about it: whom to trust and what data, say, the media should be drawing on for their reporting?”

“We are grateful to international organizations for also recording crimes against the media and journalists and speaking about it publicly. Because it is important for us that the world hears about Ukraine and sees what crimes the Russians are committing, against journalists in particular. The Russians are doing this deliberately, because a journalist’s job is to share the evidence of their crimes with the world. International organizations use different methods, which is why the data are different.

“I want to emphasize that the IMI has much more capacities to verify each case, because we live in Ukraine and have a wide contact network. We encourage international organizations to contact us if there are any contradictory details or doubts about a case. We will always help our colleagues verify the information.

“The reality is such that one must not just record that Russia has committed a crime, but also check who the victims are. Anyone can call themselves a journalist, so we find out whether this person really worked in the media. We are looking for answers to many questions: is this hypothetical person really a journalist, could they be a Russian propagandist, how did they get to Ukraine. For instance, if someone entered Ukraine’s occupied territory from Russia in violation of the law, sharing the vehicle with Russian soldiers, then who is this person? If they are injured in a shelling strike, some international organizations may count this as a crime against journalists. This is unacceptable for us.

“The differences in figures may also be due to the fact that our colleagues from international organizations only count the data from the newly occupied territories or journalists detained after 2022, not taking into account the rest of the crimes that were committed after the beginning of the war in 2014. Speaking of which, the IMI’s list of imprisoned journalists citizen journalists from Crimea who have been in custody since 2016. Overall, each case of data discrepancy is individual. We have recently launched a major effort to coordinate our data with leading global organizations defending the rights of journalists, such as Reporters Without Borders. We are confident that improving our interaction will help defend the rights of journalists more effectively.”

Documenting losses. How to document the truth while reining in the emotions

“What challenges does one face when documenting data on Russian crimes against the media?”

“We have often encountered cases where it was unclear how to categorize a journalist: as someone who died while reporting or not. We had to revisit such cases many times, contact relatives and ask what happened at the time.

“Documenting the deaths of Maks Levin and Oleksandr Makhov was very traumatic for me. I literally had goosebumps as we were releasing these news, I can still feel my hair stand on end when I think about it. I did not know Maks personally, but he was close to the IMI, we did projects together, made statements on Maks’s initiative. Sasha Makhov was a coach at IMI training classes for military intelligence officers, consulted us when developing recommendations for journalists. This is such a great loss for our community, it was very painful for everyone.”

“How do you cope when documenting deaths?”

“I try to disengage, although it very rarely works. I thought about it and realized that if I shut myself off, I won’t be able to work as efficiently. But I have to learn to do it, because every now and then it overwhelms me and I get tired of it. I work with this negative information all the time. Sports help me cope with it.

“I remember giving a speech at an event where our designer had made a large diagram with deceased journalists and data on Russian crimes. I started speaking at this public event and couldn’t hold back my tears. I start talking about the dead, I start talking about Maks Levin – and that’s it, I get a lump in my throat, I start crying. I’m still so embarrassed for crying in front of the audience. It turned out that I have witness trauma. And I didn’t even understand or realize it.”

In the three years and one month since the start of the full-scale invasion, Russia committed 829 crimes against journalists and the media in Ukraine.

A total of 268 freedom of speech violations was recorded by the IMI in Ukraine in 2024 as part of the Freedom of Speech Barometer. Of these, 155 crimes were committed by Russia in the course of its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.